Figwort Monograph

Figwort

(Scrophularia nodosa)

Also Scrophularia marilandica, Scrophularia lanceolata

Scrophulariaceae

• Common Name(s)

Knotted Figwort, Throatwort. Carpenter's Square. Kernelwort. Deilen Ddu ('good leaf, Welsh', Rose Noble), Murrian Grass, Stinking Christopher, Bull-wort, Pool-wort, Brown-wort, kernelwort, scrofula plant, escrophularia (Spanish), knoldbrunro (Danish), Knotige Braunwurz (German), scrophulaire noueuse (French)

• Personal Observations

I first met figwort in California, Scrophularia californica, nodosa’s close relative, growing along the slope above the fire road trails in the Oakland hills. Is it a Stachys? I wondered. A Lamium? No. The smell, more deep earth skunk than Stachys cat urine. And the stems, almost all square, sometimes hexagonal. Something was slightly sideways. Not quite Lamiaceae.

I’ve since met other native Scrophularia in other parts of the country, always delighted. And for years now, watched excitedly as the Scrophularia nodosa emerge strong from the ground every year, their leaf mounds slowly spreading. Hello! Welcome back to the above ground figwort!

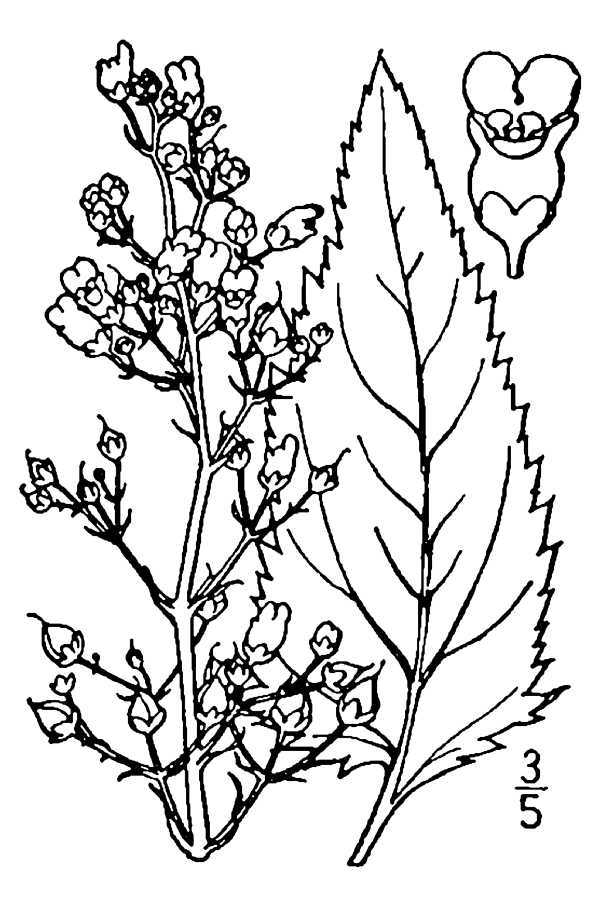

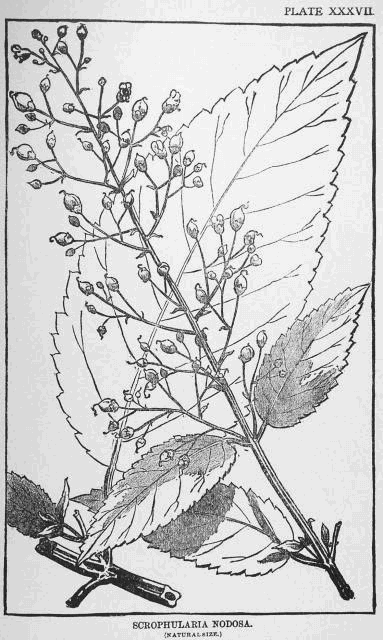

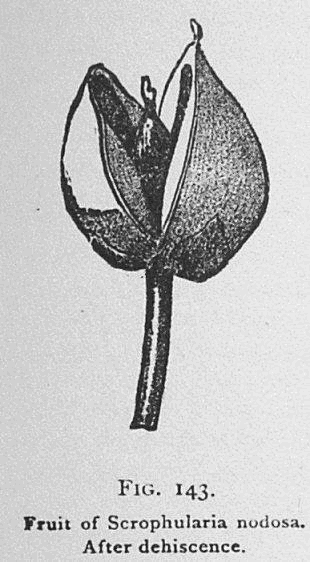

• Botanical Description

Figwort, before it flowers, looks like it could be a member of the mint family. With stems that seem square, and opposite leaves in an almost 90 degree rotation. Looking closer though, sometimes the stems are square, and sometimes they have six sides.

Then they flower, and there is no question they are a Scrophularia. The flowers are small and wonderfully strange. They are a brown/red/purple that is sometimes reflected on the stem. Bilaterally symmetrical, they are little balls that are pollinated by wasps.

These perennial plants can over time form patches, and have roots with nodes on them, reminiscent of the swollen lymph nodes they are indicated for. The smell of the leaf is like foetid rich compost, being compared to elder leaf and some species of Stachys.

Scrophularia nodosa is native to Europe, Asia, and the Middle East and has naturalized in parts of North America. Other species of Scrophularia are native to U.S. and have often been used interchangeably, although they may have variation in use, ideal part used and dosage. There are around 200 to 35o species in the Scrophularia genus, depending on who you ask, and many of them are used medicinally where they grow (Go Botany, Encyclopedia Britannica, Nature Gate, Pasadaran 2017).

• Properties

Lymphatic, Alterative, Relaxant, mildly Diuretic

• Parts Used

Above ground pre-flower or just flowering plant

• Taste

Musk, Earth, Skunk, Acrid, Bitter, Salty, Sweet.

With similarity to some Stachys, Lamium and Sambucus species

• Tissue State

Stagnant, Tense

• Degree of Action

3rd

• History

Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Database gives some folk uses of figwort from Belgium, Germany, Turkey and Spain. Figwort is used for genital warts, as a vulnerary for wounds, for abscesses, eczema, carcinomas and inflammations, as a depurative, anodyne, and diuretic (Duke).

These uses are in line with written uses through the years. There is some confusion and disagreement about the identity of plants in some of the earlier writings, with Scrophularia and Lamium species and different Scrophularia species potentially confounded up until the Renaissance.

Fig is an old word for hemorrhoids, pointing to Figworts use topically for these and other swelling. External use was common with Figwort before the 18th century. It was commonly recommended solely externally, or with a concurrent external and internal use. The term scrofula, where Scrophularia comes from, is up for debate in its more exact meaning. The definition I like best here is enlarged lymph nodes in any part of the body. It may also have applied to skin issues including rashes, and some argue that it is more specific to large swellings in the cervical glands related to tuberculosis.

Dioscorides recommended only external use of the leaves and stems,

“to dissolve indurations (hardenings), tumours, scrofulous swellings of the glands...and tumours of parotid glands...as a plaster with vinegar twice daily, the decoction as a rinse, and a plaster with salt for spreading ulcers, gangrenes and putrid humours.”

Similar recommendations were made by Fuchs, Mattioli, Pliny, Paul of Aegina and Dodoens, who also suggests internal use.

Gerard and Bauhin write of using figwort to clean, debride, and rebuild tissues wounds and ulcers. Bauhin lists the roots as the main part used, and Gerard the leaves of water figwort. Gerard, Bauhin, and Fuchs all recommend figwort as a face wash as a remedy for ailments ranging from redness of the face to deformity resembling elephantiasis. Parkinson uses the distilled water of figwort similarly for, “any foul deformity that is inveterate and the leprosy likewise.” They also all include variations on salves and ointments in butter, soft animal fat, or oil and wax for hemorrhoids, bruises, infuries, burns, strumas, tumours, painful joints, scabs, and scaly skin conditions. There seems to be a consensus during this time that the action of figwort is thinning and dispersing, although the descriptions of this vary.

The Salernital Herbal recommends figwort as an electuary for scrofula and hard glands, specifying that it be taken in the morning on an empty stomach with no food eaten for 3 hours afterwards. They also suggest preparing it in pancakes followed by some white wine. The Trotula also mentions a figwort honey preparation, useful for, “thickness of lips (Tobyn 2016).”

The Family Herbal gives figwort preparations as, “The juice of the fresh gathered root is an excellent sweetener of the blood taken in small doses, and for a long time together. The fresh roots bruised and applied externally, are said also to be excellent for the evil. They cool and give ease in the piles, applied as a pultice (Hill 1812).” This is around the time that figwort began to be talked about specifically as an internal alternative.

In the United States, Scrophularia nodosa, marilandica, and lanceolata were for a long time all considered to be nodosa, or variations of nodosa. Although numerous writers note differences in appearance, taste and smell. This may account for some of the variation in opinion of potency and efficacy of this herb among practitioners in the U.S. It is simultaneously credited with slow but powerful alterative capacity, and called weak and feeble. This may also be attributed to different preparations, with the dried root being the most common in commerce, while other writers suggest fresh leaf preparations. Specific Medication and Specific Medicines is an example of these contradictory entries.

“The Scrophularia stimulates waste and excretion, and is probably as certain in its action as any of our vegetable alteratives. Beyond this it seems to exert a marked influence in promoting the removal of cacophastic deposits. We employ it in scrofula, in secondary syphilis, in chronic inflammation with exudation of material of low vitality, and in chronic skin diseases. In the latter case it is frequently used as a local application, as well as an internal remedy.

It exerts an influence upon the urinary and reproductive organs, and has been employed in some obscure affections of these with advantage. Still it is feeble and slow, and too much must not be expected from it.”

The Physiomedical Dispensatory gives the action of figwort as, “largely relaxant, moderately stimulant, with a small portion of demulcent power; slow in action, mild, soothing, and leaving behind a fair tonic impression,” with their alterative properties focusing mainly on the mesenteries, kidneys, and skin. They suggest that the leaves are the most medicinal and say that figwort works in the urinary tract by, “moderately promoting the flow of urine, relieving torpor, and imparting a soothed and toned impression to these organs.” And praise figwort as a tonic for painful, irregular menstruation. It is found in formula with Liriodendron and Convallaria for this use. And as a syrup with yellow dock, celastrus, guaiacum, gentian, anise and sassafras oil, and rose water as a tonic for, “scrofula, cutaneous affections, secondary syphilis, etc (Cook 1869).”

The American Materia Medica gives “Specific Symptomatology” as cachexia (weakness and wasting of the body due to severe chronic illness), depraved blood, chronic glandular disorders and chronic skin diseases. Especially in, “those cases in which there is a peculiar pinkish tint, or pink and white tint to the complexion, with puffiness of the face, with full lips of a pallid character (Ellingwood, 1919).”

Around this time, figwort, never extremely popular, began to fall out of favor, being talked about in the past tense in the United States Dispensatory in 1918. “Figwort leaves were formerly considered. tonic, diuretic, diaphoretic, discutient, anthelmintic, etc.; useful in scrofula and as a local application in hemorrhoids (Remington 1918).”

(If you’re wondering what discutient means, it’s a rather lovely definition: “An agent, such as a medicinal application, that serves to disperse morbid matter (Wiktionary).”)

• Key Uses

Chronic systemic inflammation and immune system dysregulation including autoimmune issues, histamine and mast cell issues, and other atopic presentations including eczema and allergies, being potentially specific in Psoriatic Arthritis and Psoriasis.

Lymphatic and alterative support for long lasting infections

Topically and internally with swollen lymph nodes, abscesses, hemorrhoids, and ulcers, with potential specificity with poor wound healing in diabetes.

Supportive with conventional treatment as an alterative for tumors of the lymph nodes.

• Clinical Uses

External use of the root of figwort has carried through in current clinical practice. The National Botanic Pharmacopoeia suggest this form for scrofulous sores, abscesses, gangrene, sprains, swellings, inflammations, wounds and diseased parts. Priest and Priest suggest external use of the root for hemorrhoids. Chevalier recommends external use for healing wounds, burns, hemorrhoids and ulcers. Bartram suggests topical use in exudative skin eruptions, and to encourage discharge of abscesses, boils, and infected wounds.

Graeme Tobyn, despite having read of external use, until writing an in depth figwort monograph, had only used figwort internally, as an alterative in chronic skin disease, eczema, acne, psoriasis, and when, “looking for an alterative with some bite.” He recounts a case where a client had recovered from cirrhosis of the liver, who suffered from periodic intense itching, especially on the shoulders in the evening. Figwort was the remedy that brought relief. Chevalier similarly describes figwort as an herb that, “supports detoxification of the body and advises it in any skin condition with itching and irritation.” David Hoffman also uses figwort in eczema and psoriasis.

Figwort contains iridoid glycosides including harpagoside, thought to be one of the main active constituents in Devil’s Claw. Because of this sharing of constituents it has been suggested as an alternative to this plant, which is a slow growing desert plant at risk of over harvest. According to Mills and Bone, devil’s claw is used for rheumatic and arthritic pain, including muscle pain, and possibly endometriosis, and has traditional indications for digestive disturbances, febrile illnesses, allergic reactions and cardiac arrhythmias. It also has similar topical uses to figwort, being used for wounds, ulcers, boils and pain relief (Bone 2013). Faivre suggests that figwort is useful for joint pain and suggests a standardized fluid extract of the fresh plant works well for functional and arthritic joint disease (Tobyn 2016)

Michael Moore worked mostly with the native North American species. He used the fresh tincture or strong tea topically for fungal infections, eczema, rashes, burns and hemorrhoids and the above ground plant infusion internally for hives, back and chest eruptions, and as a general alterative with a mild sedative effect. He suggests it as a long-term anti-inflammatory for, “chronic, low-grade skin and mucosa sores and irritations,” suggesting, “if you get frequent cold sores or rectal aches and have a tendency for sore throats, or if you have long standing eczema with periodic acute episodes of redness and itching, try this plant and some yellow dock in the evening.” He also suggests it with balsam root for boggy arthritis aggravated by cold damp weather, and as a poultice for breast pain with PMS. He combined figwort with red root for the “slow viruses” with a tendency to enlarged lymph nodes (Moore, 2003).

An interesting case review of a homeopathic consult using the sensation method identified Scrophularia nodosa 200c for a client with IBS-D that was having fear around loss of control from his health problems and around losing loved ones. A few doses of homeopathic figwort helped lessen his diarrhea, with daily Immodium use decreased to occasional use, and fears being reduced significantly with his, “sense of security and comfort zone is greatly extending, much less anxiety, better adaptation to the stresses of life, more verbalization of emotions other than fear (Vienneau 2012).”

Laurinda Taylor lists the TCM uses of figwort as,

“Clears Heat/Cools Blood: used when Heat enters the blood level of warm-febrile diseases (Yin and Xue stages) causing bleeding, dry mouth, purplish tongue, and other similar deficient Heat symptoms as well. Nourishes Yin: fever conditions with constipation, irritability, and dry cough. Drains Fire/Relieves Toxicity: swollen or red eyes, and especially extreme cases of sore throats. Softens nodules: neck lumps due to Phelgm-Fire, sore throat pain, swollen tonsils, scrofula and swelling.”

Writing from England, she adds,

“Common figwort has sometimes been used traditionally as an herbal tea to treat the common cold and is often mixed with purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), lemon balm (Melissa officinalis), or peppermint (Mentha x piperita) (Wonky Pot Apothecary 2018) .”

Josh Muscat has recently been using higher dose figwort (60-90 drops fresh tincture of Scrophularia californica above ground plant) in formula both preventatively and after active infection of COVID-19. He feels like it has been a helpful part of his general protocol, which is changed based on client presentation (Muscat 2020).

Figwort has been overlooked and downplayed by herbalists throughout time, including now, when it is not a common remedy in the larger collective materia medica. I think this is an oversight, especially when what we are working with has been shifting more and more towards chronic systemic inflammation of varying types. In my clinical practice, this is where figwort shines. As a small part of formulation, around 10 drops/dose, I have found figwort very helpful when working with histamine issues and autoimmune issues and postulate that it could be significantly helpful in other manifestations of systemic inflammation. It is a plant that is easily grown in the garden, the above ground part of the plant effective, and is a large enough plant needed in a small enough dose that a few plants can provide someone with enough medicine. I have preferred fresh tincture of above ground pre-flower, or just beginning to flower, plant, similar to what I generally prefer in many Lamiaceae plants. I think of it as a rather strong alterative and lymphatic appropriate for long term use. I have, like Graeme Tobyn, focused mostly on internal use, and am excited to try combined internal and external application based on what I’ve learned here.

• Studies

A 2013 study with authors from China and Germany looked at the effect of Diosmin, a flavonoid found in figwort, on the blood-retinal barriers and their tight junctions in rats.

Diosmin was first isolated from Scrophularia nodosa in 1925 and used as a medication first in 1969. It has been found to be a vascular protecting agent with mechanisms of action listed as, “improvement of venous tone, increased lymphatic drainage, protection of capillary bed microcirculation, inhibition of inflammatory reactions, and reduced capillary permeability.” It has also been looked at for its therapeutic potential in treatment of IBD (Salaritabar 2017).

The study induced ischemia and inflammation in the rat retinas. This study goes into some fascinating physiology about the inflammatory process in the blood-retina barrier and tight junctions that I won’t go into here, but is worth a read if you’re into that sort of thing. One interesting take away: zonulin works in the tight junctions of the blood retina barrier in a seemingly similar way to the tight junctions of the small intestine. The study found that diosmin reversed retinal edema, retinal functional injury, damage to the structure of tight junctions, loss of blood retinal barrier integrity, and obvious retinal microvascular hyperpermeability when given intragastrically at a rate of 10mg/kg of powder in a saline solution 30 minutes before the purposeful injury of the retina, and daily afterwards until the rats were killed (Tong 2013).

A 2018 Iranian study looked at the potential anti-malarial of different constituents in 3 native species of Scropularia, S. frigida, S. subaphylla, and S. atropatana. They found that the dichloromethane extractions of all three species of Scrophularia tested showed potent antimalarial effects, with S. frigida showing the strongest activity and that the n-exane extracts showed moderate antimalarial effects. They found high amounts of flavonoids and terpenoids in the DCM extract, and steroids in the n-hexane extracts. They posited that,

“the presence of cardiac glycosides with their steroidal moiety might be effective in the potency of DCM and n-hexane extracts. In addition, it is assumed that the flavonoids and coumarins which existed in DCM extract may be lipophilic types (for instance, methoxylated or methylated things). Furthermore, according to Table 3, GC-MS analysis of volatile parts of DCM and n-hexane extracts showed high amounts of diterpenoids and steroids in S. frigida, respectively.”

Interestingly, they are studying the antimalarial properties of these plants because of the decreasing effectiveness of chloroquine and artemisinin (from Artemisia annua) preparations due to resistance to these drugs, yet are still searching for single consitituent drug possibilities instead of looking for potential whole plant preparations that could potentially be less susceptible to resistance (Afshar 2018).

• Constituents

Iridoid Glycosides including Harpagoside, Aucubin, Catalpol

Phyenylpropanoids

Flavonoids including Diosmin and Acacetin Rhamnoside.

A review of constituents of the Scrophularia genus and potential biological activities: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6130519/

• Dosage and Method of Delivery

Topical in all the forms you can imagine preparing it in any parts of the plant except the seed. (everyone and their mother)

Fresh Tincture (1:2, 95% etoh) above ground just beginning to flower plant. In formula 5-30 drops to 5x/day (personal clinical experience)

Specific Scrophularia 5 to 30 drop doses (Ellingwood, 1919)

2-8 g dried herb 3x/day (British Herbal Pharmacopoeia)

• Cautions and Contraindications

“No information on the safety of figwort in pregnancy or lac- tation was identified in the scientific or traditional literature. Although this review did not identify any concerns for use while pregnant or nursing, safety has not been conclusively established (Gardner, 2013).”

There are at least theoretical contraindications for figwort with cardiac issues because of its relation to Digitalis and concern over some similar constituents. The Botanical Safety Handbook believes these concerns to be only theoretical in nature.

Harvest figwort before any seed formation begins, as the seeds could be toxic (Remington, 1918).

• References

Grieve, M (1936) A Modern Herbal. https://botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/f/figkno13.html

Go Botany. Scrophularia nodosa https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org/species/scrophularia/nodosa/

Encyclopedia Britannica. Figwort Plant Genus. https://www.britannica.com/plant/figwort

Nature Gate. Figwort. http://www.luontoportti.com/suomi/en/kukkakasvit/figwort

Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Database, Scrophularia nodosa https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:4KR4nnpfXX8J:https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/ethnoPlants/ethnoBotanyList/1807.pdf%3Fmax%3D18%26offset%3D0%26sort%3Dactivity.activity%26order%3Dasc%26filter%3D0%26count%3D18%26ubiq%3D+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us&client=safari

Tobyn, G et al. (2016) The Western Herbal Tradition. Singing Dragon Publishers. P. 297-306

Hill, J (1812) The Family Herbal. https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/hill/figwort.html

Scudder, J (1870) Specific Medication and Specific Medicines. https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/spec-med/scrophularia.html

Cook, W (1869) They Physiomedical Dispensatory https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/cook/SCROPHULARIA_NODOSA.htm https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/cook/LIRIODENDRON_TULIPIFERA.htm https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/cook/RUMEX_CRISPUS.htm

Ellingwood, F (1919) The American Materia Medica, Therapeutics and Pharmacognosy. https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/ellingwood/scrophularia.html

Remington, J et al. (1918) The Dispensatory of the United States of America. https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/usdisp/scrophularia.html

Bone and Mills (2013). Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy. 2nd Edition. Churchill Livingston Elsevier.

Moore, M (2003). Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West. Museum of New Mexico Press.

Vienneau, R (2012). Scrophularia Nodosa Case of Irritable Bowel Disease

Case Illustration of Multi Dimensional Healing using the Sensation Level within the Noumedynamic Method. http://www.michmontreal.com/scrophularia-nodosa-case-of-irritable-bowel-disease/

Wonky Pot Apothecary (2018). Figwort. https://thewonkypotapothecary.wordpress.com/2018/06/12/figwort/

Muscat, J (2020). Personal communication with Josh Muscat.

Tong, A N et. al (2013) Diosmin Alleviates Retinal Edema by Protecting the Blood Retinal Barrier and Reducing Retinal Vascular Permeability during Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury

Salaritabar, A et al. (2017) Therapeutic potential of flavonoids in inflammatory bowel disease: A comprehensive review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5537178/

Afshar, F et al. (2018) Screening of Anti-Malarial Activity of Different Extracts Obtained from Three Species of Scrophularia Growing in Iran. Iran Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5985184/

Gardner, Z et al. (2013) The American Herbal Products Association’s Botanical Safety Handbook 2nd Edition. https://s3.amazonaws.com/thinkific-import/5076/AmericanHerbalProductsAssociationsBotanicalSafetyHandbook2ndEd11529438093468-1559675898898.pdf